I want to know what you, specifically you, mean when you say “male gaze”. Not what you think other people mean—what it means to you.

I loved “Poor Things”. I don’t often like movies. I usually find they could have been a short film or really needed to be a whole series, tv style. Friend after friend told me they either thought I’d love it—due to one facet or another, none of which they would disclose in detail for fear of spoilers—or wanted to know my thoughts. So I watched.

I felt seen.

I recognized other women I’ve known.

And men, too.

One of the problems with “colloquial male gaze”, as opposed to film theory’s definition, is that it’s amorphous. We all think we know what it means, but it means something different for everyone who uses it.

So, when we’re talking about “Poor Things”, or pornography, or erotic photos (like those of female photographer Shelbie Dimond), I want to know what “male gaze” means to each person who deploys the phrase. I want them to go deeper, to carve out the definition of their term.

———

Octavio Winkytiki, who I knew nearly two decades ago during his career as a pin-up photographer, recently popped up in the “tagged” section of my Instagram account with photos from the first time we’d worked together. The shoot was a real shoot but done for the benefit of a Canadian TV station. I’d been a fan of his art for a few years, and jumped at the opportunity to be photographed by him. Winkytiki’s ModernVixens work was bright, showed women as strong, and told a story.

He was a weird dude.

I’d become accustomed to good artists being weird people.

I was, and still am, a weird person myself.

For part of the day, Winkytiki had me posing on a backyard couch. It was a home for spiders. I was afraid of spiders. Somewhere in storage in Canada is footage of me navigating the tension between my desire to avoid the spiders and my desire to be professional and also get the shots that I knew would look amazing.

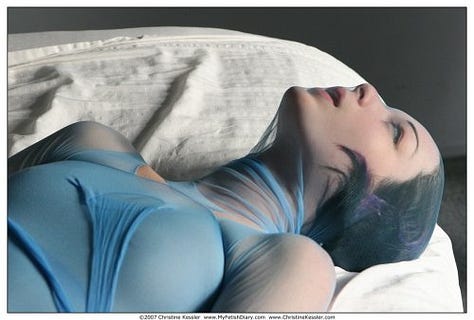

I was already being photographed by Christine (steeneeweenee) Kessler by that time. I had to maneuver, socially, to get the opportunity to work with her, and I no longer recall how I managed. She was a lifestyler herself—a person who enjoyed kink, fetish, and BDSM in her personal life, as opposed to merely working in those areas. She preferred to work with models who were also lifestylers.

Steen’s work was bright, incorporated latex in colors, with patterns and frills, and featured models who seemed pleased to be there. Like Octavio’s photos, Steen’s often told a story, and showed women as strong even when they were portrayed submissively.

Her photos were like nothing I’d ever seen before.

They changed the visual range of fetish photography.

I partially yet significantly credit Steen with ushering in the era of Katy Perry in quirky candy themed latex mini dresses.

I had seen kink, fetish, and BDSM as merely part of the constellation of sexuality since I first learned anything beyond “tab A into slot B creates babies”. I partook, often gleefully, and had learned, in the kink scene, to navigate consent of others, understand my yeses, nos, and maybes, and to communicate those clearly.

At the time, when people heard “fetish photography”, they tended to imagine something akin to what people seem to mean when they say “male gaze”—colloquially, that is. They imagined the photographer was male, which was sometimes the case and sometimes not. They took issue with objectification and sexualization, when photography inherently makes subjects into objects and sexualization was what we were there to do. We, meaning including myself. And I would have been disappointed to not be sexualized.

———

Throughout my career in adult entertainment, from the first days of pin-up, art nude, and fetish modeling to the attempts to co-found successful web platforms, I was learning about sex. I was gaining access to props and experiences I wouldn’t have been able to afford or arrange in my personal life.

Meanwhile, I was subject to rhetoric from a type of feminists who—as Nadine Strossen recently said to Elizabeth Nolan Brown of Reason—“expressly equate women with children in the laws and in their writing, so that those of us who think that we enjoy sex, let alone those who think that we would enjoy looking at or even, heaven forbid, performing for or creating pornography”.

So if you see the movie, you’ll see why I love it.

You might see things that are worthy of criticism, too.

But if you want to critique it to me, I’ll need you to define “male gaze”.

I’ll need you to acknowledge, like Steen did, my agency.

And I’ll need you to accept my boundaries, like Winkytiki, while making space for me to be brave.